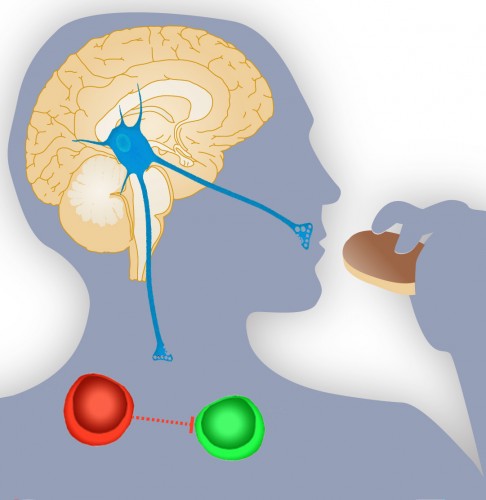

At first glance, the nervous system and the immune system seem like independent entities: the nervous system monitors and controls bodily functions through the neural electrical network, while the immune system chemically reacts against “non-self” particles. However, in reality, all systems of the body work together to maintain a delicate homeostasis and are interrelated in ways often yet-to-be-explained by research.

A recent study serves as a perfect example of this integration of systems. Dr. Tamas L. Horvath, Professor of Neurobiology and Chair of the Section of Comparative Medicine at the Yale School of Medicine, and his team have experimentally linked hunger suppression in mice to increased probability of incurring the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis in predisposed individuals. This result also suggests that drugs used for weight-loss could lead to undesirable consequences in the immune system.

An experimental model using knockout mice was utilized to observe the system. First, hunger suppression in the mice had to be induced. This was achieved by using mice that lacked a certain gene, which caused the mice to have a decreased appetite. The mice were then tested for immune system response. The findings suggest that apparent behavioral traits that are under neural control, such as hunger and emotion, have an undeniable impact on immune function: in this case, in promoting the onset of autoimmune diseases.

It is surprising to note that the greatest obstacle in this particular study was not related to the experiments. Rather, Dr. Horvath stated that the interest in interdisciplinary research spanning these apparently unrelated fields was low since there did not seem to be any apparent connection between his area of study, obesity and hunger, and immune function. However, the insight that this study provides on immune function could fundamentally change the field of immunology, suggesting that this interdisciplinary project was a success.

According to Dr. Horvath, “the next step is to determine immune response in conditions of acute hunger suppression.” What would happen to T cell response if the subject does not eat for a few days, and how is the overall health of an individual impacted by such fleeting behaviors? The potential value of such a study is enormous because the results could indicate whether decreased appetite by personal choice is also detrimental to immune function, and therefore whether behavioral traits under an individual’s control are a factor in immune system response. In such a case, Dr. Horvath predicts, “modulating behavior could result in immune system enhancement.” The real implications do not only pertain to hunger control and autoimmune disease, but also to the introduction of a new area of study connecting overall immune response to any number of nervous-system-controlled behavioral patterns.