On March 17th this year, the excitement of St. Patrick’s Day paled in comparison to that of researchers at the South Pole, where the National Science Foundation-funded BICEP2 (Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization) team caught the first sign of gravitational waves from the Big Bang. The discovery is the first direct evidence supporting the theory of inflation.

Contrary to the notion that the universe has always been expanding at a constant rate, the theory of inflation proposes that the universe expanded very rapidly in the first 10-34 seconds after the Big Bang. It was first proposed in 1980 by Alan Guth, Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. If confirmed, inflation will have significant implications on how we describe the birth and development of our universe. And though the theory still requires additional supporting evidence, the BICEP2 discovery provides a step in the right direction.

Analogous to electromagnetic waves which result from wiggling charges, the gravitational waves that hint at the inflation theory are generated by shaking masses, which oscillate substantially under high-energy conditions such as those of the earliest universe. Although Einstein’s equation of general relativity has long predicted their existence, previous detection efforts have proved largely fruitless. “This has been like looking for a needle in a haystack, but [this time] instead we found a crow bar,” said BICEP2 project collaborator Clem Pryke of the University of Minnesota, to Discovery.

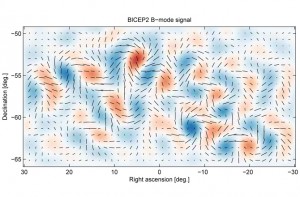

The researchers found evidence of gravitational waves by studying leftover light, called cosmic microwave background (CMB), from the Big Bang. They observed a unique pattern, called primordial B-mode polarization, which is a telltale sign of gravitational waves. “Gravitational waves interacted with photons in the universe to make them polarize in this pattern called the B-mode,” explained Charles Baltay, Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics at Yale. “The detected pattern is only allowed for gravitational waves — not electromagnetic waves, which are imprinted in a form of E-mode.”

Besides this historic detection of gravitational waves, researchers also found a surprisingly high ratio —nearly 5 to 1 — between B-mode and E-mode patterns. This high proportion is evidence for a significant amount of gravitational waves formed in the early universe, greatly surpassing the estimate of the Big Bang theory without inflation. A gradually expanding universe cannot lead to such a high intensity of B-mode patterns. A much more rapid expansion, on the other hand, may account for this phenomenon.

“If confirmed to be correct,” said Baltay of the BICEP2 results, “this is a very important result.” And while efforts are currently underway to confirm the presence of gravitational waves, the March 17th discovery is heartening. “There’s a chance it could be wrong, but I think it’s highly probable that the results stand up,” said Guth in an interview with Scientific American. This finding opens doors for researchers to unravel one of the most fundamental questions the Big Bang. If the theory of inflation holds, it would yield exciting results about the mechanism behind the awakening of our universe.

The author would like to thank Professor Baltay for providing expert guidance on the theoretical concepts behind this topic.